“There was a time when most things were nature, most was habitat. And you were trying to connect a couple of towns by a road—that was the corridor of that day. Now most things are human, and we need to connect the fragments of nature and habitat with nature corridors.” – Mitch Friedman, Conservation Northwest

For Kootenay wildlife, highway traffic can be life-or-death as they negotiate through thousands of vehicles and trains.

Over 1,600 animals, mostly deer and elk, are killed every year on the Highway 3 corridor through our East Kootenay mountains—and this only represents those that are reported. This is on top of an unknown, yet likely substantial, number of animals that are killed by trains.

Something has to change to keep people and wildlife safe.

The Elk Valley is an area of particular concern. The valley forms crucial migratory bird habitat, and is critical habitat for grizzly bears, wolverines, deer, elk and a host of other wildlife. It is part of North America’s most intact wildlife and wilderness corridors—the last remaining area where large animals can roam freely between Canada and the United States. It is also one of the busiest transportation corridors in British Columbia, with commuter, recreational and commercial traffic, in addition to railway routes operating at full capacity.

Despite Highway 3 slicing through this important wildlife corridor, animals still need to cross—as they have for centuries. Animals must cross to access food, find mates, escape predators, or find shelter. They need room to roam. But when their pathways are separated by highways and railways, it presents a major barrier to movement.

Photo: National Park Service

In the East Kootenays, wildlife populations are in steep decline.

Data from the Fish and Wildlife Branch show that in the past ten years, elk populations have declined by 53 per cent; since 2006, moose populations have declined by over 50 per cent; and since 2005, mountain goat populations have reduced by 38 per cent.

Vehicle-related mortalities are adding to such sharp wildlife declines. Road-kill brings an immediate and direct effect on a population, with reductions in population seen within one or two animal generations. This is in addition to how the highway can isolate animals into island populations, limiting their ability to find mates, reducing their gene pool and bringing them one step closer to extinction.

Getting animals safely across roads and railways is a key part of connecting wildplaces and protecting wildlife populations.

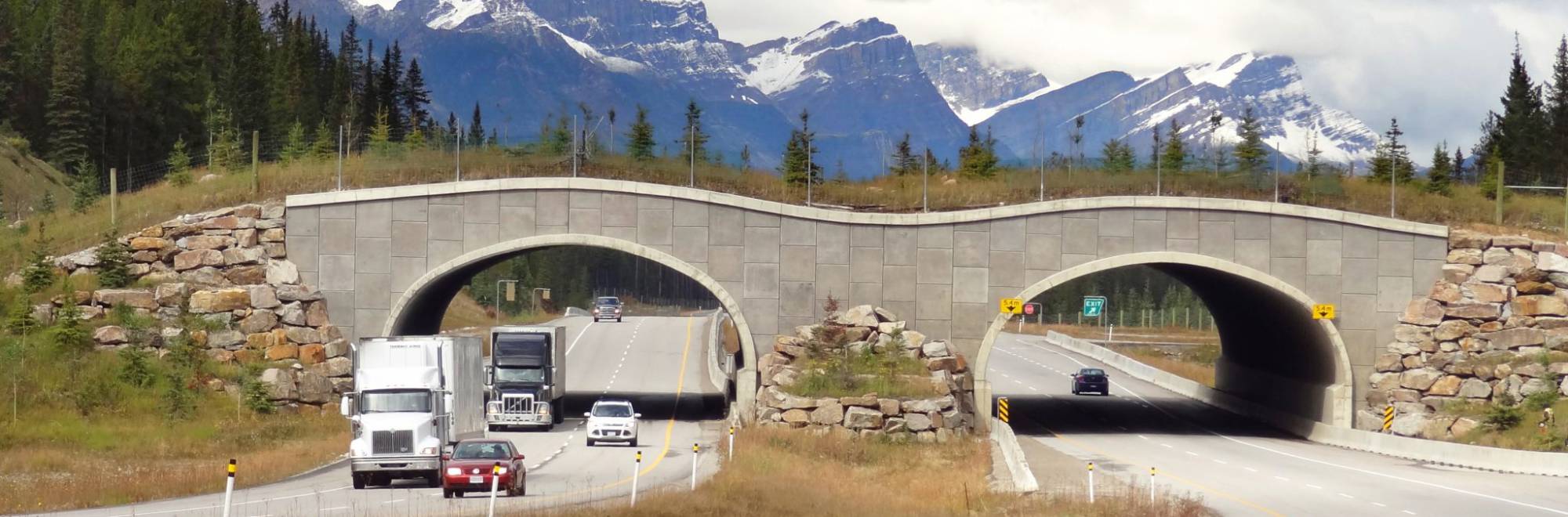

There are proven ways to coexist with wildlife, where both humans and nature can thrive. Wildlife under- and over-passess, with associated fencing, have been remarkably successful in decreasing collisions.

Essentially, overpasses are bridges for wildlife, and underpasses serve as tunnels for water and wildlife. These wildlife crossings aren’t just about saving individual animals—they’re about species survival too. Robust wildlife populations should be the norm in the East Kootenay, but recently they are starting to become the exception.

One of the most looked to examples of crossing structures are the efforts in Banff National Park. Over the past 20 years, highway fencing and crossing structures across the Trans-Canada Highway that have decreased wildlife-vehicle collision mortalities by a whopping 80 per cent. We have also learned how animals use these crossings—for example which animals prefer open crossing structures and which prefer constricted crossings with less light and more cover, and even preferences of male vs female populations.

We know that sometimes an animal uses a crossing just once—to migrate or find mates, while others use them daily (think: breakfast on one side, lunch on the other). We know that crossing structures are successful, that animals learn to use them (some immediately, and others follow suite over time), and crossings are economically beneficial—preventing vehicle-wildlife collisions saves the province and communities money.

In all: crossing structures enable wildlife connectivity, reduce our impact on nature and increase the safety of drivers.

Photo: Karsten Heuer

Now is the time for local governments to take a leadership role in convening all levels of government and First Nations for a sustainable solution to vehicle-wildlife collisions.

Examples of key mitigation strategies include:

- Dialogue with transportation planners, scientists and all levels of government to establish solutions to wildlife-vehicle collisions on the highway and railways.

- Collecting better quality wildlife mortality and tracking data to identify and support areas for crossings.

- Instituting mandatory wildlife mortality reporting for CP Rail and adopting railway wildlife mitigation measures, including employing best practices used in the national parks.

- Building wildlife overpasses, underpasses and exclusion fences where required to allow wildlife to safely cross highways and railways.

- Implementing wildlife strategies when undertaking new roadwork, including twinning highways and installing new bridges.

The work has begun.

Right now, Wildsight and our partners are updating a 2010 report identifying specific collision zones and solutions to reduce collisions along Highway 3, such as the use of wildlife overpasses and fencing. This report will reflect the current situation of animal movement and traffic flow, providing the framework for action going forward, including recommendations for government.