Imagine a pine tree.

You’re probably thinking of a tall, skinny, fast-growing lodgepole pine, like the ones that cover so much of the Kootenay landscape. But lodgepole pine aren’t our only pine. Hidden high up in the mountains or on dry, rocky slopes in valleys in the Purcells and the Rockies, limber and whitebark pine are everything the lodgepole pine is not. Slow-growing and often gnarled, these five-needled pine species are ancient and beautiful.

Today, limber pine are under threat from white pine blister rust, a disease that has moved quickly into Kootenay trees, with the infection rate increasing from approximately 25% to 90% in many areas over the last decade.

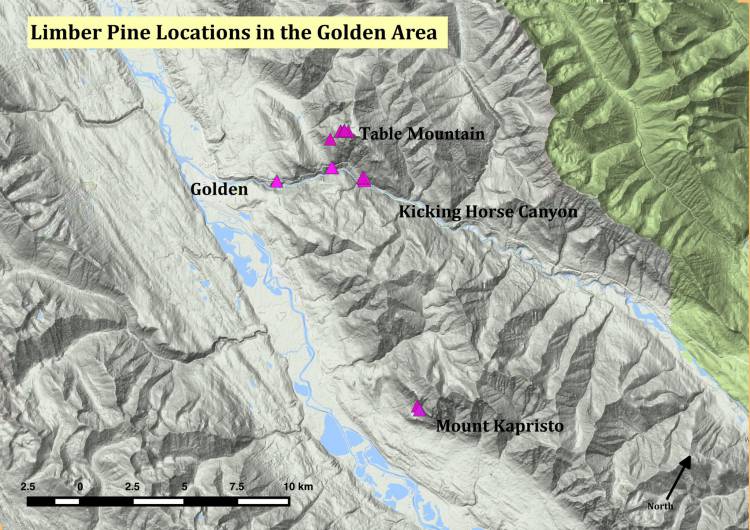

Since last year, Wildsight Golden branch’s Limber Pine Project has been mapping local limber and whitebark pines in the lower Kicking Horse Valley and spreading the word about these special trees. By putting more five-needled pine locations on the map and assessing the health of local trees, we’re taking some early steps to protect them.

“I was pretty excited when we found a large stand of limber pine on Mt. Kapristo that wasn’t on any maps yet,” says Corinna Strauss, Limber Pine Project coordinator.

While the endangered whitebark pine is found scattered across BC at high elevations, limber pine range extends into BC from the US only as far north as Golden and only on the slopes of the Rocky Mountains. Over the border in Alberta, the oldest known limber pine is roughly a thousand years old, and many-centuries-old trees are common. These pines have even been used as a climate record, with their growth rings telling us stories of conditions long ago.

“Around Golden, we find whitebark pine up on mountain ridges, generally above 1800m, while limber pine is found anywhere from valley bottom all the way up to 2000m,” says Strauss, “particularly in dry, rocky soil, like in the Kicking Horse Canyon.”

Five-needled pines, with their energy-dense seeds, are keystone species that feed birds and small mammals. Grizzly bears, ever the opportunists, dig up cone caches built by red squirrels and gorge themselves on the oil-rich seeds to fatten up for the winter. With big annual variations in seed productivity, studies have found that grizzly-human interactions are fewer when grizzlies are drawn to higher elevations to feed on abundant pine seeds. Pine seeds were also an important traditional food source for indigenous people.

The Clark’s nutcracker extracts seeds from their cones and helps the five-needled pines reproduce and disperse by stashing their seeds in the soil. Seeds that the birds don’t retrieve will often germinate, growing into new pines!

White pine blister rust: a slow killer

Both limber and whitebark pines are endangered in Canada, and white pine blister rust is the main culprit. An invasive spore from Asia with a complicated life cycle often using paintbrush as an intermediate host, the blister rust appears as a neon orange fungus on pines that disrupts the bark, eventually girdling the tree and killing it. The cankers formed secrete sugary sap that attracts rodents who chew on the tree, making the situation worse. It may take a while to kill a mature tree, but for pines that are only a decade or two old, the end can come quickly.

To understand how limber pine are faring in face of the disease, Corinna started two tree health transects, establishing lines through stands down in the Kicking Horse Canyon and higher up on Table Mountain that will be studied every five years to measure tree health.

Oops! I just cut down an endangered species

“With more and more trails being pushed up into the mountains, we’re concerned that trail-building crews might accidentally cut down whitebark pine,” says Strauss.

This year, Lake Louise Ski Area is in court facing charges under the Species At Risk Act for cutting down endangered whitebark while brushing on the ski hill, no doubt a case of the workers on the ground simply not knowing what they were cutting. Corinna will be reaching out to local trail-building crews to make sure they know how to identify whitebark pine—and that it’s a crime to cut even a single one.

“I want to thank the small crew of dedicated volunteers who joined me on field days last year to help map limber pine around Golden,” adds Strauss. “The first step to protect these special trees is simply knowing where they are.”

So next time you’re out hiking and you see a gnarly pine tree, count the needles. If they come in bundles of five, you’re in the presence of a tree that just might be older than your great-great-great-grandparents.